Chase debit card skimmed? Chase won’t protect you

Debit card skimming is a fairly common occurrence these days, meaning that at least several times a year I hear about it happening in the general area where I live. We’ve reported on why debit cards are not as well protected as credit cards in a past post, and this story confirms that fact precicely.

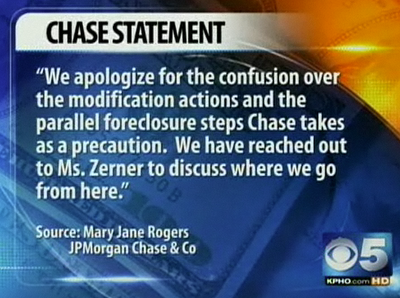

Details: I had and still have possession of my ATM card. On the 27th and 28th of last month 2 separate ATM withdrawals of $500 each were taken out of my account by hackers. On the 28th when I tried to use my card at a local merchant it was declined. Almost simultaneously I received a voicemail from Chasebank fraud division. I returned their call immediately and answered all their questions. They said my $1000 would TEMPORARILY be put back into my account pending their investigation. 5 HOURS later I was informed by ChaseBank fraud department that they had concluded their investigation AND THEY WERE NOT GOING TO REIMBURSE ME THE $1000 THAT WAS S T O L E N FROM MY ACCOUNT!!!

Why? Their 2 reasons: 1.) the 2 withdrawals were made in the same geograhical area in which I live. 2). there were no bad pin tries.

Of course, those reasons simply don’t add up with the reality of Chase’s very own ATMs being fitted with skimmers on occasion. First, if your card is skimmed, it is very likely that local thieves are to blame and they will use it in your local area. Second, if your card is skimmed, they will have your PIN number. In any case, what idiot thief would take a debit card for which they did not have the PIN and try random PIN numbers at an ATM.

In this particular case, what Chase called the same geographical area turned out to be two places each more than 100 miles from where the customer lived.

Why does Chase do things like this that are so obviously out of touch with reality? Until some insider leaks some emails that confirms that Chase frequently denies debit card fraud claims not because they don’t believe it is fraud but because they know they can get away with it, we’ll just have to speculate that is the reason.